Features - Fall 1997

The Disappearing Dance of the Sage Grouse

By R.F. Russell

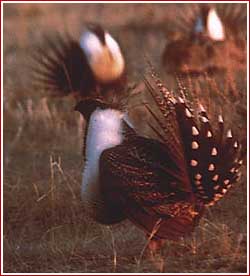

The large body size, black abdomen, white air sacs, pointed tail feathers and sage habitat make the sage grouse one of the most interesting among its prairie cousins. The large body size, black abdomen, white air sacs, pointed tail feathers and sage habitat make the sage grouse one of the most interesting among its prairie cousins.

These birds have fallen in numbers over recent years and are currently under the watchful eye of wildlife managers throughout their range. These birds have fallen in numbers over recent years and are currently under the watchful eye of wildlife managers throughout their range.

Soon after the snow disappears, the male grouse descend from the wintering grounds to relatively open, not dense sage cover. These areas often exhibit a flattened clear area of various expanses depending on the number of birds using the site. The sage grouse exhibits a complex hierarchy that includes male to male interaction, and male to female dominance ending with copulation. Soon after the snow disappears, the male grouse descend from the wintering grounds to relatively open, not dense sage cover. These areas often exhibit a flattened clear area of various expanses depending on the number of birds using the site. The sage grouse exhibits a complex hierarchy that includes male to male interaction, and male to female dominance ending with copulation.

The dancing grounds are obvious by the abundance of droppings and the presence of some feathers, a result of charging their opponents and fighting. The dominant cock bird will attempt to maintain a central territory with subordinate and younger males located outside the core. I'm not sure I can describe the sound of male sage grouse dancing and stomping during the breeding season. It is an unmistakable sound once you have heard the performance of North America's largest grouse. There are a number of scratching sounds, rattling and some plopping, none of which seem to travel over great distances. The dancing grounds are obvious by the abundance of droppings and the presence of some feathers, a result of charging their opponents and fighting. The dominant cock bird will attempt to maintain a central territory with subordinate and younger males located outside the core. I'm not sure I can describe the sound of male sage grouse dancing and stomping during the breeding season. It is an unmistakable sound once you have heard the performance of North America's largest grouse. There are a number of scratching sounds, rattling and some plopping, none of which seem to travel over great distances.

For the past two springs, Alberta Environmental Protection has been testing the methods used in monitoring the sage grouse populations. Workers want to determine which of the two survey styles provide the best information for population estimates. Should they conduct a lone survey of each strutting ground during peak activity in late April or monitor these grounds weekly for one month? For the past two springs, Alberta Environmental Protection has been testing the methods used in monitoring the sage grouse populations. Workers want to determine which of the two survey styles provide the best information for population estimates. Should they conduct a lone survey of each strutting ground during peak activity in late April or monitor these grounds weekly for one month?

Because of sage grouse behavior and the varying numbers of males visiting leks (Scandinavian term for gathering area), other jurisdictions recommend four surveys of each lek during the period of April 10 to May 10. Sage grouse surveys are required to verify that the data collected represents a reliable indicator of the population trend. Future monitoring will adopt the better of the two techniques. Because of sage grouse behavior and the varying numbers of males visiting leks (Scandinavian term for gathering area), other jurisdictions recommend four surveys of each lek during the period of April 10 to May 10. Sage grouse surveys are required to verify that the data collected represents a reliable indicator of the population trend. Future monitoring will adopt the better of the two techniques.

In the past two spring seasons, all known sage grouse locations have been monitored closely during the April dancing period. These leks are visited in the evening to allow the observer to determine an easy access point to the site. Sometimes the male grouse are present in evenings, but not always. There may not be as great a number as the following pre-dawn count period. Sage grouse are early birds. Their routines begin well before most staff are prepared to work. In the past two spring seasons, all known sage grouse locations have been monitored closely during the April dancing period. These leks are visited in the evening to allow the observer to determine an easy access point to the site. Sometimes the male grouse are present in evenings, but not always. There may not be as great a number as the following pre-dawn count period. Sage grouse are early birds. Their routines begin well before most staff are prepared to work.

It is amazing to observe the behavior in sight and sound once there is enough light to locate the participants. They seem to appear from nowhere and are active in pre-dawn to approximately a half-hour after sunrise. Often the sub-adults are the first to leave the lek to begin foraging somewhere within three kilometres of the site. They will fly off but regularly just walk away. It is amazing to observe the behavior in sight and sound once there is enough light to locate the participants. They seem to appear from nowhere and are active in pre-dawn to approximately a half-hour after sunrise. Often the sub-adults are the first to leave the lek to begin foraging somewhere within three kilometres of the site. They will fly off but regularly just walk away.

We have 32 areas in southeastern Alberta where these year-round residents have been recorded dancing in the past. Some of these sites have not had grouse present in the past 20 seasons. We have 32 areas in southeastern Alberta where these year-round residents have been recorded dancing in the past. Some of these sites have not had grouse present in the past 20 seasons.

Sagebrush is a key factor in the grouses' ecology. Adult sage grouse consume up to 100 per cent sage in their winter diet. Broods are hatched from the seven to eight eggs per nest. Chicks consume an insect diet for the first 11 weeks, then gradually switch to a sage diet. Only 50 percent of the nests are estimated to be successful. Populations of 500 to 600 males observed in 1981 have declined to 132 males in 1996, and 113 males in 1997. These specimens are located on just seven of the historical leks. There appears to be plenty of potential at most of the inactive areas but something is wrong. Sagebrush is a key factor in the grouses' ecology. Adult sage grouse consume up to 100 per cent sage in their winter diet. Broods are hatched from the seven to eight eggs per nest. Chicks consume an insect diet for the first 11 weeks, then gradually switch to a sage diet. Only 50 percent of the nests are estimated to be successful. Populations of 500 to 600 males observed in 1981 have declined to 132 males in 1996, and 113 males in 1997. These specimens are located on just seven of the historical leks. There appears to be plenty of potential at most of the inactive areas but something is wrong.

Sage grouse population counts do not include an estimated female count because often the females only visit the lek on one occasion. It would not be practical to count females due to the time required. The overall decline in population causes a lot of concern. Habitat alteration, loss and deterioration have been the primary reasons for the drop in numbers. Other factors including poaching, predators, nest destruction, drought, climatic change, cyclic phenomenon, too much disturbance and perhaps unknown causes are also suggested. The answers even after 30 years of spring monitoring have not been determined. The presence of concerned bird watchers and photographers may also represent a disturbance. All factors have a cumulative effect. Sage grouse population counts do not include an estimated female count because often the females only visit the lek on one occasion. It would not be practical to count females due to the time required. The overall decline in population causes a lot of concern. Habitat alteration, loss and deterioration have been the primary reasons for the drop in numbers. Other factors including poaching, predators, nest destruction, drought, climatic change, cyclic phenomenon, too much disturbance and perhaps unknown causes are also suggested. The answers even after 30 years of spring monitoring have not been determined. The presence of concerned bird watchers and photographers may also represent a disturbance. All factors have a cumulative effect.

What are the chances of survival for this prairie bird? In 1996 the hunting season was eliminated in Alberta. The hunting season had been in place since 1967 but it was not considered to be a major factor in the decline. The province of Saskatchewan, which has never had an open season, has also indicated a population decline from high numbers in the past to only 44 males recorded in 1996, and a further 60 per cent drop in 1997. Continued monitoring and expansion of the study will be required to provide more information to understand the causes of population decline. There will hopefully still be time and money available to unlock the mystery. Long-term projects of the scope and duration required to provide answers often cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and there just doesn't seem to be enough to go around. What are the chances of survival for this prairie bird? In 1996 the hunting season was eliminated in Alberta. The hunting season had been in place since 1967 but it was not considered to be a major factor in the decline. The province of Saskatchewan, which has never had an open season, has also indicated a population decline from high numbers in the past to only 44 males recorded in 1996, and a further 60 per cent drop in 1997. Continued monitoring and expansion of the study will be required to provide more information to understand the causes of population decline. There will hopefully still be time and money available to unlock the mystery. Long-term projects of the scope and duration required to provide answers often cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and there just doesn't seem to be enough to go around.

Sage grouse are a species at risk and need recovery assistance. They have been classed as a threatened species by COSEWIC. It would be most disturbing to have another prairie grouse species disappear in barely 60 years. Sage grouse are a species at risk and need recovery assistance. They have been classed as a threatened species by COSEWIC. It would be most disturbing to have another prairie grouse species disappear in barely 60 years.

R.F. Russell is a wildlife technician with Natural Resources Service at Brooks, AB.

|

![[Game Warden Archives]](photo/logo2.gif)